Preview

Transcription

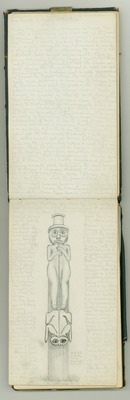

stable enough to allow a tree to take root in it, or to keep it a month if it were rooted in it. Oct. 26: Sunday, and of course we remain in camp. This weather is still rainy, but I set out up the Sound to observe. Half a mile from camp I found more dead wood, and on the lee side of the rocky knob 50 or 60 feet above the sea I discovered a number of stumps and a section showing the roots in situ with black leaf mould underneath. This is a telling discovery, and shows beyond doubt that these naked hills were forested and that the timber we find along the shore and buried in soil was not derived from a distance but simply was avalanched from the heights above. The whole of the mor[aine] soil once stationary is now on the move, and all the timber has slid off just as the rubbish accumulated on the snow-covered roofs of houses in winter is shed off in the spring thaw. But what change has come upon this glacial soil to make it shift so universally when it has been for hundreds of years stable? And how comes it that no remnants of the forest are to be found on rocky ridges where the trees could cast anchor independent of soil. In the first place the present climate is warmer and wetter, less snow and more rain, and furthermore the gl[acier]s while they filled all the channels and wombs and hollows of the mountains would act as damn holding the soil on the protruding ridges and rock tops in place. That the climate is warm[er] is shown by the melting shrinking condition of the gl[acier]s, and it is plain that were formerly much snow fell to thaw off gradually, incessant flood-rains would fall, saturating the soil, causing it to decay and become slippery and wash it off. It is in this condition now. It was not in this condition while the forests existed. As to the absence of forest remnants on the soilless ridges. In this region near the fountains of the great gl[acier]s every spot where trees could grow was covered with soil. Pushing on over two lofty ridges that terminate in bald promontories I gained some noble views of five gl[acier]s that pour their crystal floods directly into the salt water. One of these, the nearest is only about five ms. from camp. The clouds hang low, veiling the higher portions of the fountains, but every now and then I gained glimpses of a wide sea of ice in which the mountains rise like islands in the white expanse. The day has been and is sternly stormy. The snow is about 3 feet deep on the highest ground reached by me, 1500 ft. above sea. On a rough avalanche slope covered with snow I had a trying time, and in climbing along the face of a slippery cliff was put to my mettle as a mountaineer several times. My limbs had been sleeping in the boat. This day they were awakened. Crossed 10 or 12 foamy streams in which the surging and booming and roar of the water was mixed with the thud and bump and rumble sounds of the bowlders that they were carrying. Every stream was also muddy as if mining operations were being actively carried on above. I never before saw so hasty and so universal a movement of soil. Every place was raw as a mine where gravel banks were being sluiced away by the hydraulic method. I got back to camp at dusk. The Indian asked Mr. Young whether I was seeking gold, and when he was told that I was only seeking knowledge Toyatte said I was a witch to seek it in ice and storms. He did not like {sketch: 20 ft high at Kuke Village Kuprinoff [ Kupreanof] Island}

Date Original

1879

Source

Original journal dimensions: 11.5 x 18 cm.

Resource Identifier

MuirReel26Journal01P17.tif

Publisher

Holt-Atherton Special Collections, University of the Pacific Library

Rights Management

To view additional information on copyright and related rights of this item, such as to purchase copies of images and/or obtain permission to publish them, click here to view the Holt-Atherton Special Collections policies.

Keywords

John Muir, journals, drawings, writings, travel, journaling, naturalist