Little Manila also offered entertainment in the evenings. Pool halls, dance clubs, and cockfights provided a reprieve from hard farm labor. During the mid-20th Century, social clubs like the Rizal were known for their jazz musicians who performed both original and covers of American and Filipino music. Taxi girls enjoyed dancing the foxtrot, waltz, and other styles of dance.

In a region that placed high demand on their labor, Filipinos found themselves navigating a strictly segregated Stockton. North of Main Street, white-owned businesses posted signs warning “Positively no Filipinos Allowed.” As a result, Little Manila became a vital center of commerce and community for Filipinos, geographically mixed with Japanese and Chinese communities.

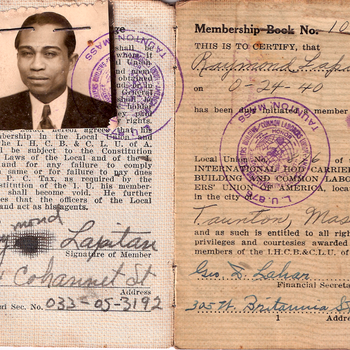

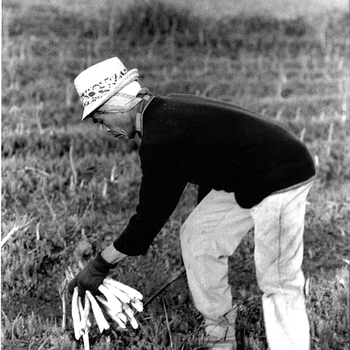

The San Joaquin-Sacramento Delta’s mild climate offered agricultural laborers year-round work. In the 1920s Congress’s immigration restrictions on Chinese and Japanese workers placed Filipinos in high demand among asparagus growers. Asparagus farm work was grueling and often resulted in very little pay, which resulted in the formation of various labor unions based in Little Manila. Despite their hardships in agriculture, Filipinos still hoped to have a better future for themselves and their families.

Filipino restaurants served a variety of Filipino dishes such as adobo and lumpia. The Lafayette Lunch Counter, leased and managed by Pablo “Ambo” Mabalon, was among those that not only became a place for homesick Filipinos to get a taste of the Philippines, but also served as a permanent mailing address for itinerant labors and graciously offered a credit system to struggling Filipinos.